No one, except a few pedants, enjoys working on chemical nomenclature. However, accurate and widely-accepted nomenclature is a vital need for communication amongst more than academic chemists. For example, politicians writing treaties and customs officers inspecting trade goods need to know exactly what materials they are dealing with. It is now generally accepted that IUPAC should be responsible for providing this kind of nomenclature for the world to use. IUPAC chemical nomenclature is widely-regarded as the world standard. When a nomenclature question arises, the first reaction is often: what is the name that IUPAC gives? Principles of Chemical Nomenclature is an attempt to show people how to find the name they require, but it also explains the misunderstandings that may arise before such a process is complete.

No one, except a few pedants, enjoys working on chemical nomenclature. However, accurate and widely-accepted nomenclature is a vital need for communication amongst more than academic chemists. For example, politicians writing treaties and customs officers inspecting trade goods need to know exactly what materials they are dealing with. It is now generally accepted that IUPAC should be responsible for providing this kind of nomenclature for the world to use. IUPAC chemical nomenclature is widely-regarded as the world standard. When a nomenclature question arises, the first reaction is often: what is the name that IUPAC gives? Principles of Chemical Nomenclature is an attempt to show people how to find the name they require, but it also explains the misunderstandings that may arise before such a process is complete.

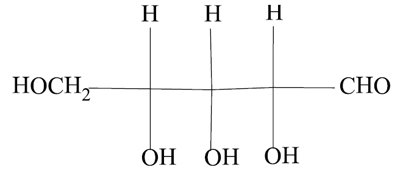

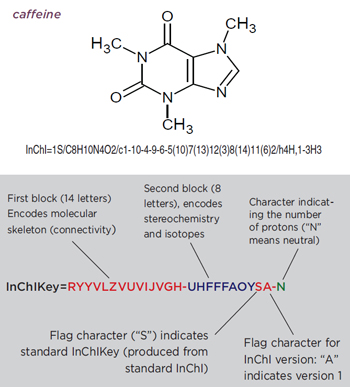

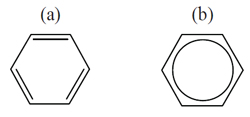

In the first place, there is no monolithic construction called IUPAC Nomenclature. Nomenclature is a subject that has grown and changed over the years. The first widely accepted systematic nomenclature proposals arose in France amongst Lavoisier and his colleagues in the 1780s, and they were dealing with what today we recognise as inorganic compounds. Internationally-accepted systematic nomenclature may be reckoned to stem from the Geneva Congress of 1892. These nomenclatures attempted, and still attempt, to be systematic, but the systems they use are different. Consequently the methodologies employed in deriving the names of inorganic and organic compounds are generally different. [See box for examples.]

| Examples of changes over time are many, and some are cited here. It sometimes takes time for such changes to be assimilated!

—The nitroprusside ion should now be called systematically pentacyanidonitrosylferrate(2–). —Ferric, ferrous and stannic and similar forms should be replaced by iron(II), iron(III) and tin(IV), and so on. —Propylene is no longer a recommended name for C3H6, which is now simply propene. —n-butane should now be called just butane, though isobutane is still allowed. —Butanol is the name for an alcohol with the OH group bound to an end carbon atom of a linear saturated four-carbon chain, but isobutanol is not an allowed name when the OH group is bound to a terminal carbon of the parent isobutane. Then the molecule should be called 2-methylpropan-1-ol. |

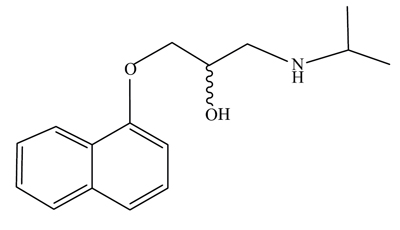

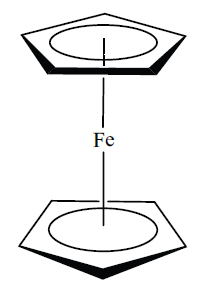

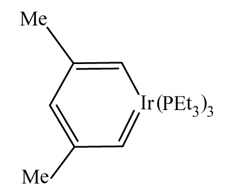

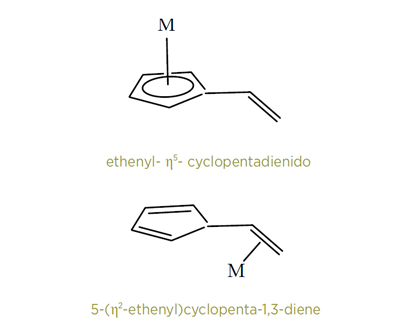

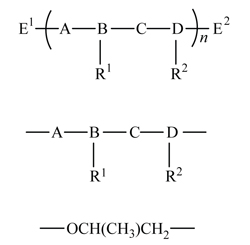

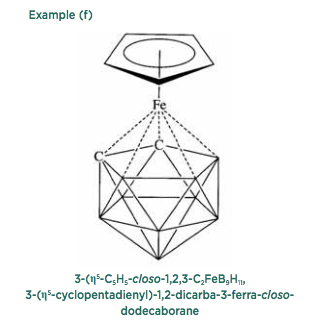

In the second place, there are more systems sheltered under the IUPAC umbrella, such as that for polymers, and also systems to deal with newer materials such as organometallic compounds, which may be regarded as falling into more than one category of compound, and may require the use of more than one system, or even a specially-modified system, to name them satisfactorily.

In the third place, studies related to chemistry, such as biochemistry, pharmacy, and cosmetics, have developed their own specific nomenclatures, which may be abbreviated and modified for commercial purposes, and these can also produce unequivocal names, but not names which necessarily convey the complete structural information usually required by IUPAC nomenclatures. However, IUPAC is usually involved jointly with other international bodies in the elaboration of these systems.

— {first published as ref 2}

This blogpost provides short notes and briefs about Principles of Chemical Nomenclature – A Guide to IUPAC Recommendations. Each section addresses a specific topic such as systematic nomenclature, the constructing of names, or the use of abbreviations. Nomenclature Notes were first published in Chem Int, from March 2012 to Dec 2013 <https://iupac.org/publications/ci/indexes/nomenclature-notes.html>

The author, Jeffery Leigh is the editor and contributing author of Principles of Chemical Nomenclature—A Guide to IUPAC Recommendations, 2011 Edition (RSC 2011, ISBN 978-1-84973-007-5) [overview given in ref 1]. He has been an active contributor to IUPAC nomenclature since 1973.